Use cross-platform browser features to build sign-in forms that are secure, accessible and easy to use.

Updated

If users ever need to log in to your site, then good sign-in form design is

critical. This is especially true for people on poor connections, on mobile, in

a hurry, or under stress. Poorly designed sign-in forms get high bounce rates.

Each bounce could mean a lost and disgruntled user — not just a missed sign-in

opportunity.

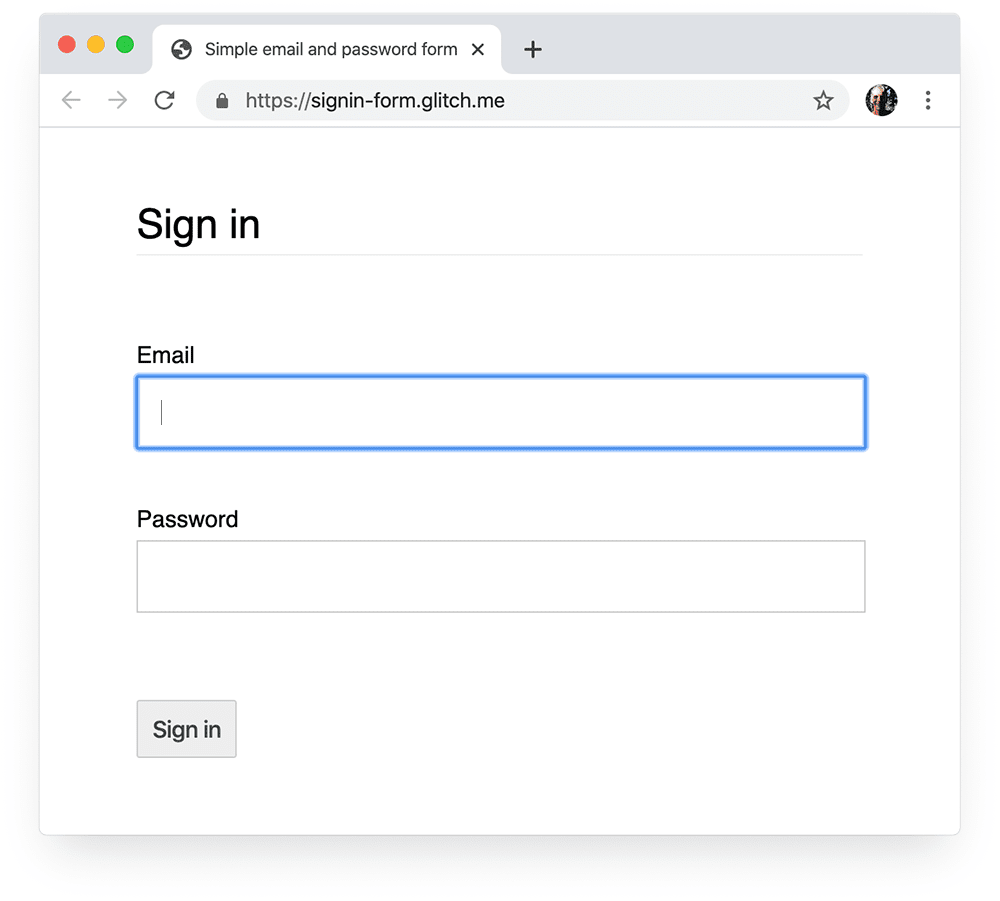

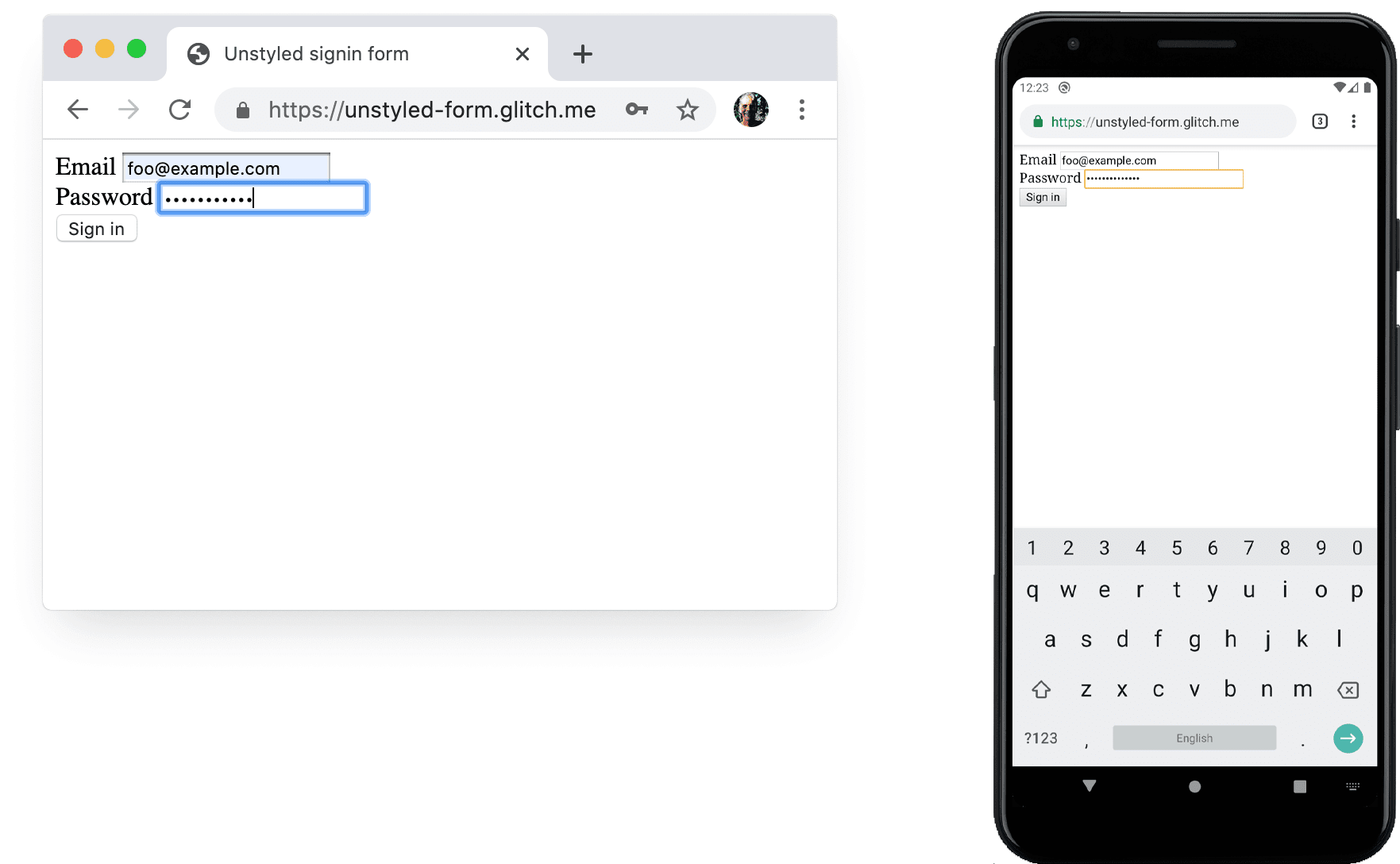

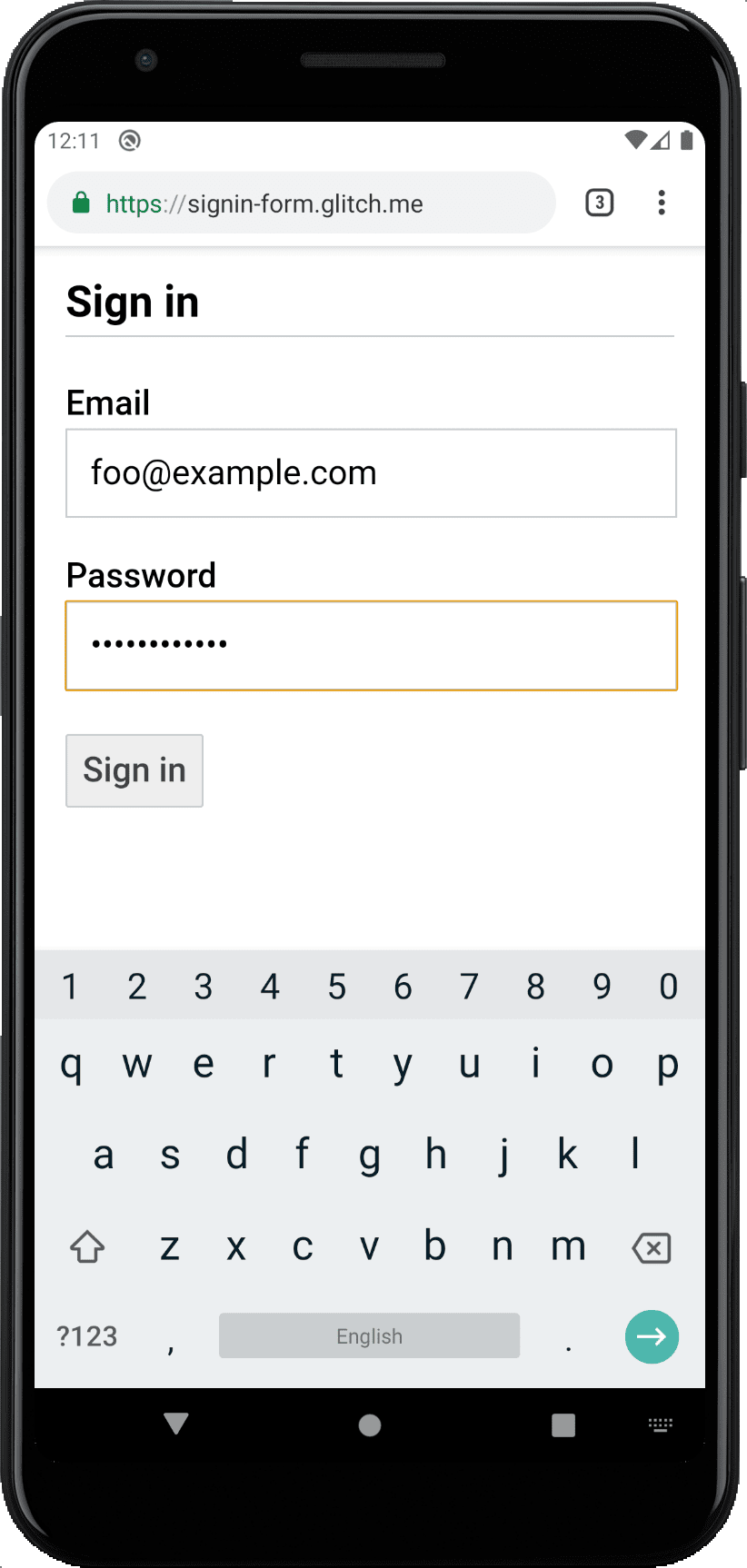

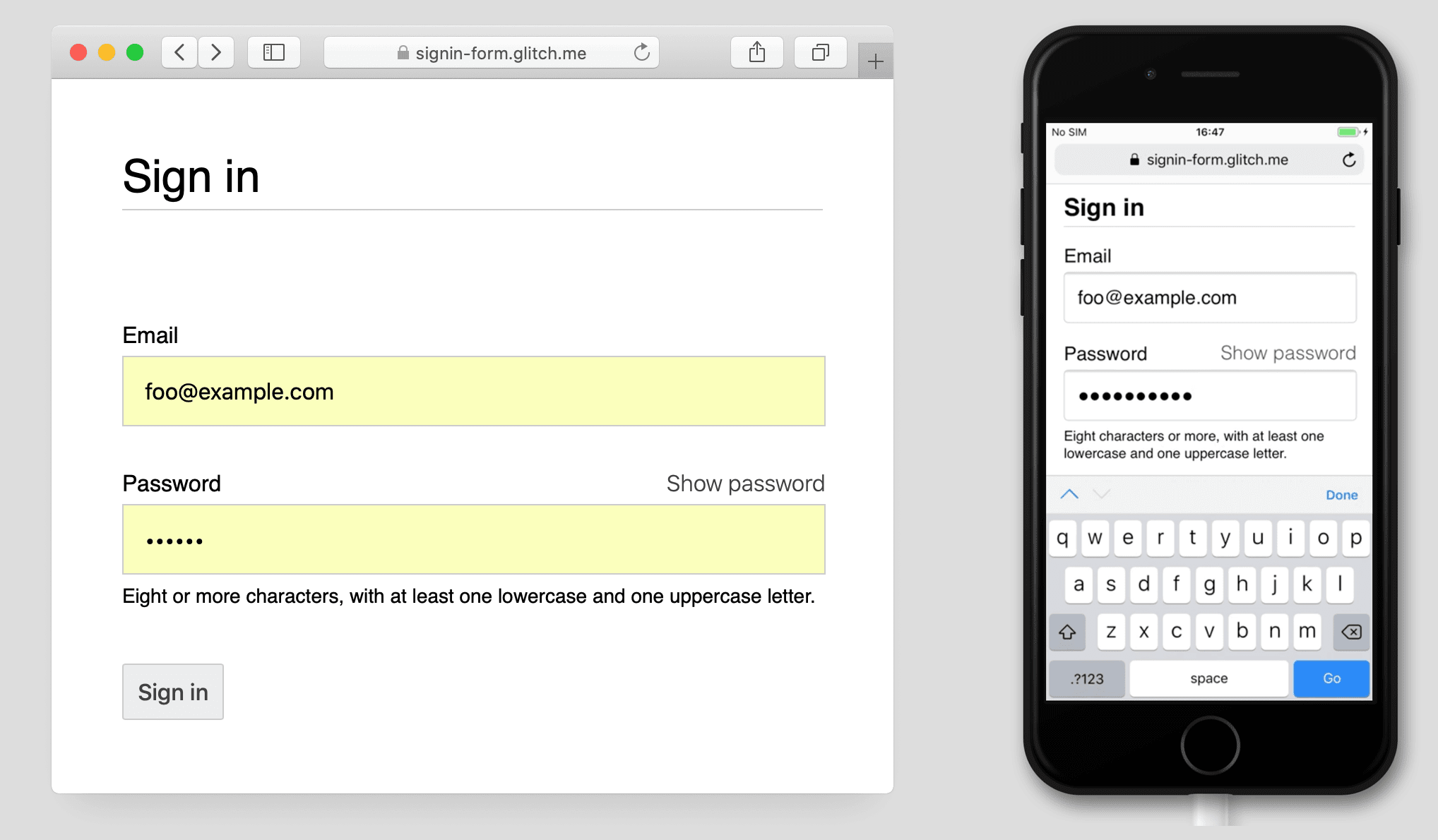

Here is an example of a simple sign-in form that demonstrates all of the best practices:

Check list

- Use meaningful HTML elements:

,,

, and. - Label each input with a

. - Use element attributes to access built-in browser

features:type,yam,autocomplete,required,

autofocus. - Give input

yamandgoattributes stable values that don't change

between page loads or website deployments. - Put sign-in in its own element.

- Ensure successful form submission.

- Use

autocomplete = "new-password"for the password input

in a sign-up form, and for the new password in a reset-password form. - Use

autocomplete = "current-password"for a sign-in

password input. - Provide Show password functionality.

- Use

aria-labelandaria-describedbyfor

password inputs. - Don't double-up inputs.

- Design forms so the mobile keyboard doesn't obscure inputs or

buttons. - Ensure forms are usable on mobile: use readable text,

and make sure inputs and buttons are large enough to work as touch targets. - Maintain branding and style on your sign-up and sign-in pages.

- Test in the field as well as the lab: build page analytics,

interaction analytics, and user-centric performance measurement into your

sign-up and sign-in flow. - Test across browsers and devices: form behavior varies

significantly across platforms.

This article is about frontend best practices. It does not explain how to build

backend services to authenticate users, store their credentials, or manage their

accounts. 12 best practices for user account, authorization and password

management

outlines core principles for running your own backend. If you have users in

different parts of the world, you need to consider localizing your site's use of

third-party identity services as well as its content.

There are also two relatively new APIs not covered in this article which can

help you build a better sign-in experience:

- Web OTP: to deliver one-time passcodes or

PIN numbers via SMS to mobile phones. This can allow users to select a phone

number as an identifier (no need to enter an email address!) and also enables

two-step verification for sign-in and one-time codes for payment confirmation. - Credential Management: to enable developers to store and retrieve password credentials and federated credentials programmatically.

Use meaningful HTML

Use elements built for the job: , and . These enable

built-in browser functionality, improve accessibility, and add meaning to your

markup.

Use

You might be tempted to wrap inputs in a <div> and handle input data

submission purely with JavaScript. It’s generally better to use a plain old

element. This makes your site accessible to screenreaders and other assistive

devices, enables a range of built-in browser features, makes it simpler to build

basic functional sign-in for older browsers, and can still work even if

JavaScript fails.

A common mistake is to wrap a whole web page in a single form, but this is liable

to cause problems for browser password managers and autofill. Use a different

for each UI component that needs a form. For example, if you have

sign-in and search on the same page, you should use two form elements.

Use

<label for="email">Email</label>

<input go="email" …>Two reasons:

- A tap or click on a label moves focus to its input. Associate a label with an

input by using the label'sforattribute with the input'syamorgo. - Screenreaders announce label text when the label or the label's input gets

focus.

Don't use placeholders as input labels. People are liable to forget what the

input was for once they've started entering text, especially if they get

distracted (“Was I entering an email address, a phone number, or an account

ID? »). There are lots of other potential problems with placeholders: see no

Use The Placeholder

Attribute and

Placeholders in Form Fields Are

Harmful if you're

unconvinced.

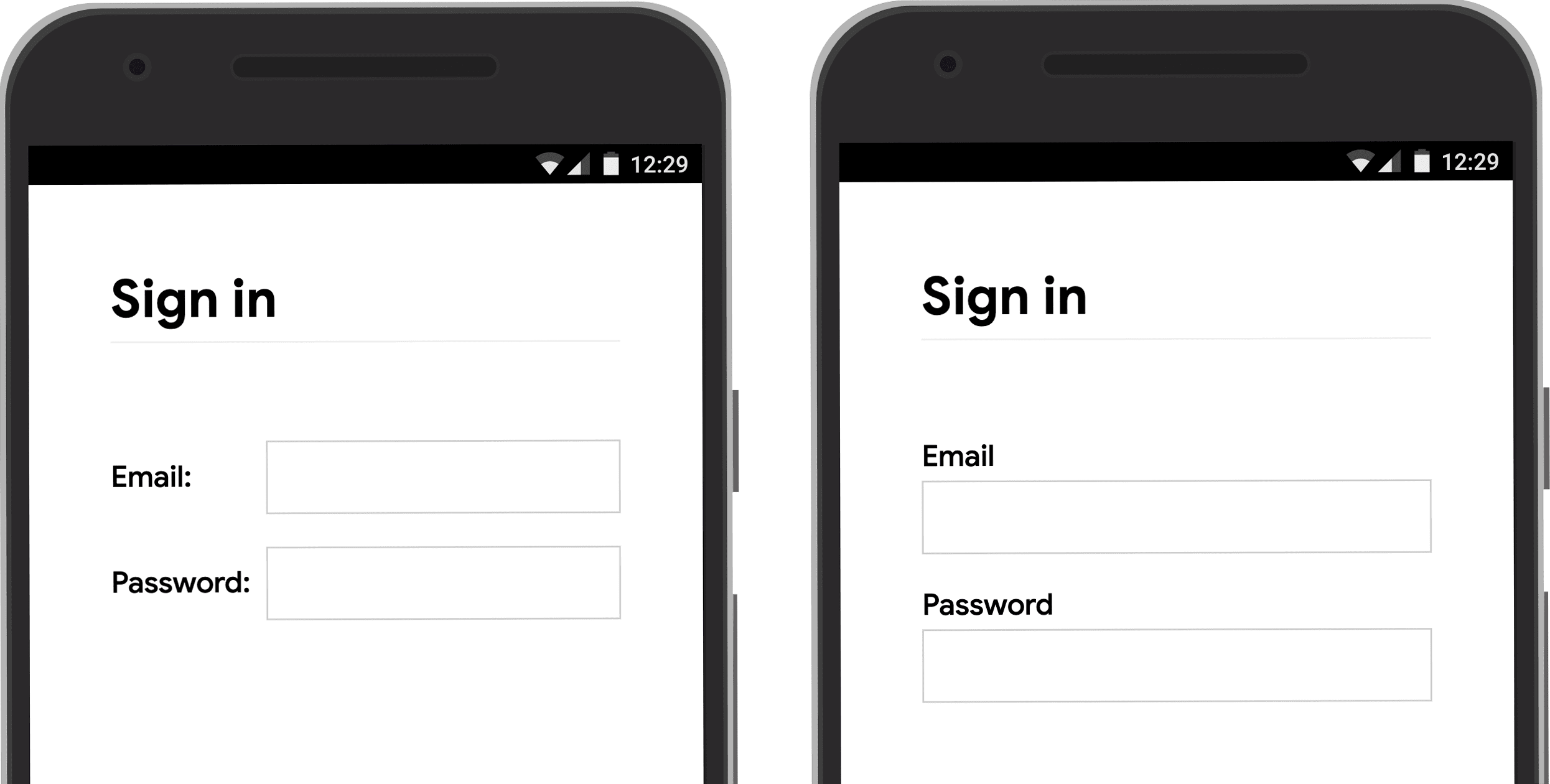

It's probably best to put your labels above your inputs. This enables consistent

design across mobile and desktop and, according to Google AI

research,

enables quicker scanning by users. You get full width labels and inputs, and you

don't need to adjust label and input width to fit the label text.

Open the label-position Glitch on a

mobile device to see for yourself.

Use

Use

for buttons! Button elements provide accessible behavior and built-in form

submission functionality, and they can easily be styled. There's no point in

using a <div> or some other element pretending to be a button.

Ensure that the submit button says what it does. Examples include Create account or

Sign in, not Submit or Start.

Ensure successful form submission

Help password managers understand that a form has been submitted. There are two

ways to do that:

- Navigate to a different page.

- Emulate navigation with

History.pushState ()orHistory.replaceState (),

and remove the password form.

With an XMLHttpRequest or fetch request, make sure that sign-in success is

reported in the response and handled by taking the form out of the DOM as well

as indicating success to the user.

Consider disabling the Sign in button once the user has tapped or clicked

Item. Many users click buttons multiple times

even on sites that are fast and responsive. That slows down interactions and

adds to server load.

Conversely, don't disable form submission awaiting user input. For example,

don't disable the Sign in button if users haven't entered their customer

PIN. Users may miss out something in the form, then try repeatedly tapping the

(disabled) Sign in button and think it's not working. At the very least, if

you must disable form submission, explain to the user what's missing when they

click on the disabled button.

Caution:

The default type for a button in a form is submit. If you want to add another

button in a form (for Show password, for example) add type = "button".

Otherwise clicking or tapping on it will submit the form.

Don't double up inputs

Some sites force users to enter emails or passwords twice. That might reduce

errors for a few users, but causes extra work for there users, and increases

abandonment

rates.

Asking twice also makes no sense where browsers autofill email addresses or

suggest strong passwords. It's better to enable users to confirm their email

address (you'll need to do that anyway) and make it easy for them to reset their

password if necessary.

Make the most of element attributes

This is where the magic really happens!

Browsers have multiple helpful built-in features that use input element attributes.

Help users start faster

Add an autofocus attribute to the first input in your sign-in form. That makes

it clear where to start and, on desktop at least, means users don't have to

select the input to start typing.

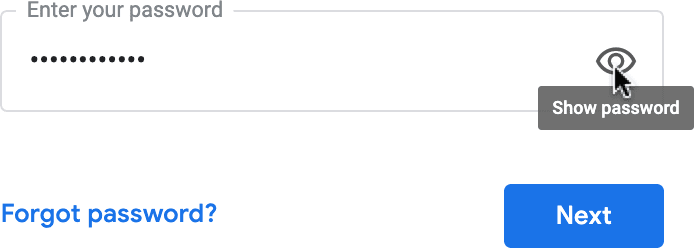

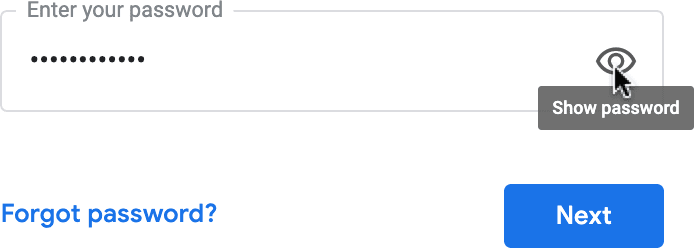

Keep passwords private — but enable users to see them if they want

Passwords inputs should have type = "password" to hide password text and help the

browser understand that the input is for passwords. (Note that browsers use

a variety of techniques to understand input roles and decide

whether or not to offer to save passwords.)

You should add a Show password icon or button to enable users to check the

text they've entered — and don't forget to add a Forgot password link. See

Enable password display.

Give mobile users the right keyboard

Use to give mobile users an appropriate keyboard and

enable basic built-in email address validation by the browser… no JavaScript

required!

If you need to use a telephone number instead of an email address, enables a telephone keypad on mobile. You can also use the

inputmode attribute where necessary: inputmode = "numeric" is ideal for PIN

numbers. Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About

inputmode

has more detail.

Caution:

type = "number" adds an up / down arrow to increment numbers, so don't use it for

numbers that aren't meant to be incremented, such as IDs and account numbers.

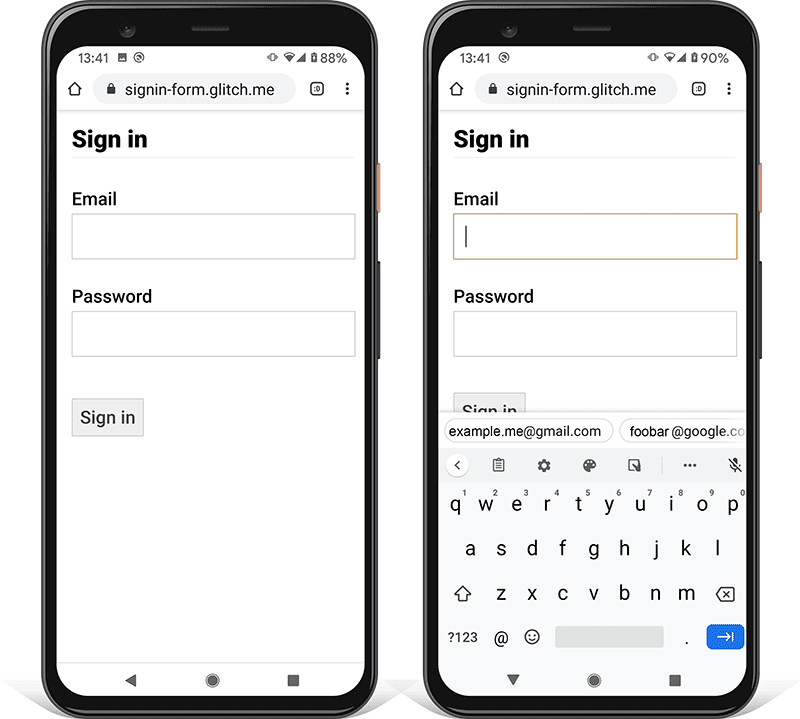

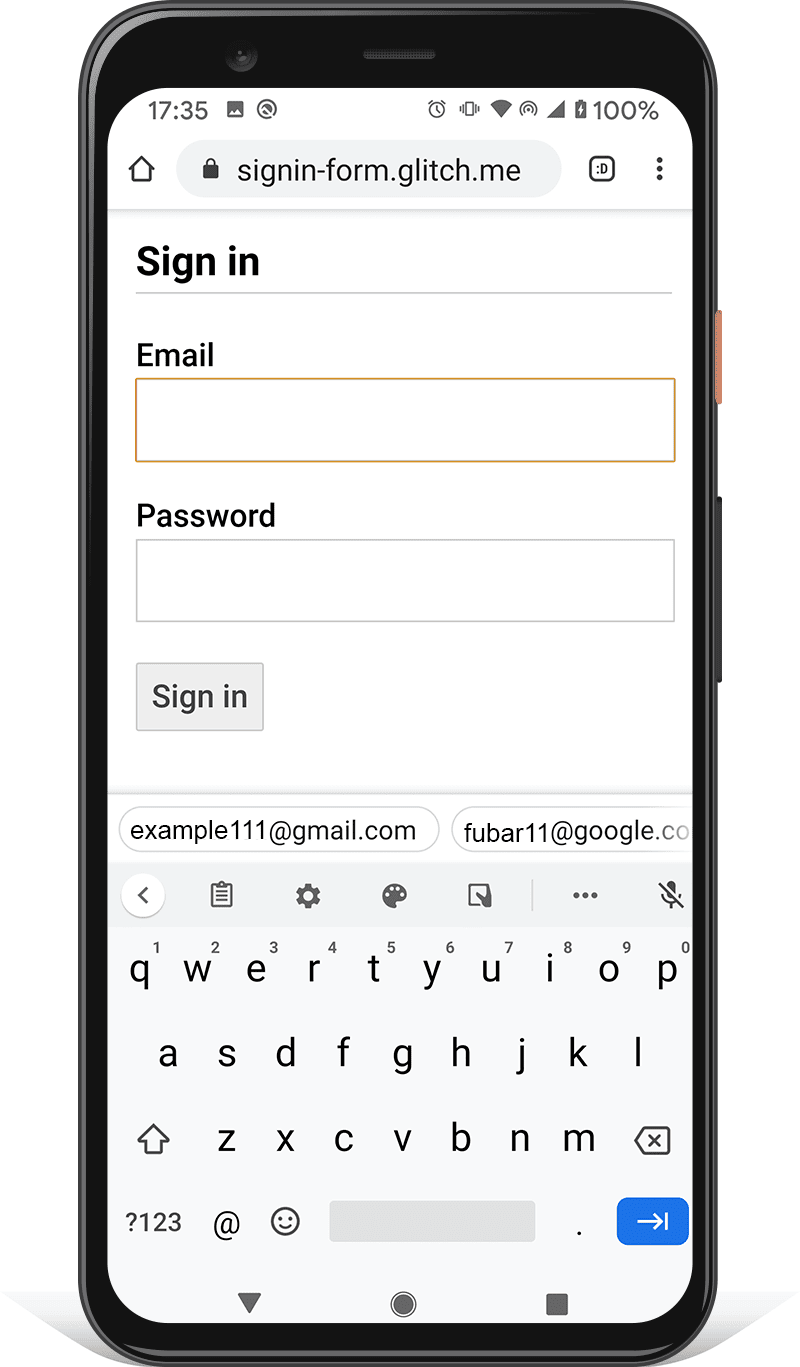

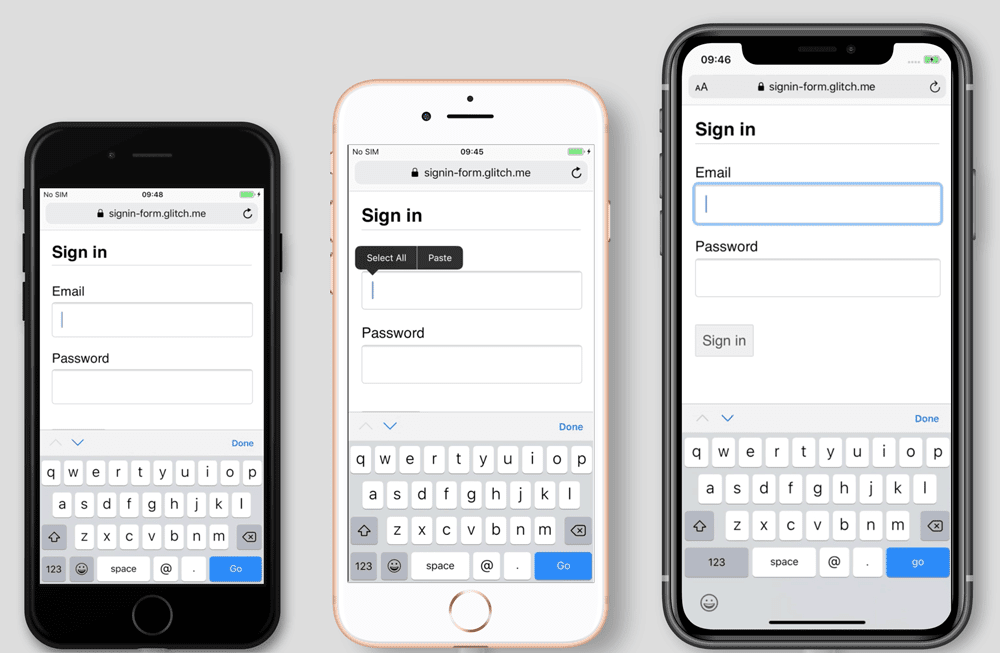

Prevent mobile keyboard from obstructing the Sign in button

Unfortunately, if you're not careful, mobile keyboards may cover your form or,

worse, partially obstruct the Sign in button. Users may give up before

realizing what has happened.

Where possible, avoid this by displaying only the email/phone and password inputs and Sign in button at the top of your sign-in page. Put other content below.

Test on a range of devices

You’ll need to test on a range of devices for your target audience, and adjust

accordingly. BrowserStack enables free testing for de Open Source

projects on a range of real devices

and browsers.

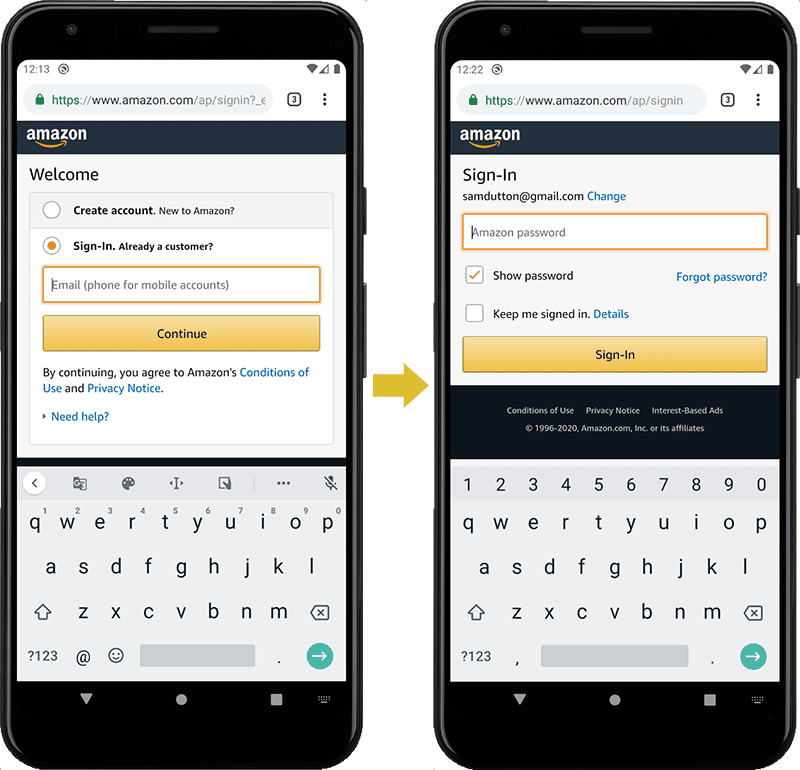

Consider using two pages

Some sites (including Amazon and eBay) avoid the problem by asking for

email/phone and password on two pages. This approach also simplifies the

experience: the user is only tasked with one thing at a time.

Ideally, this should be implemented with a single . Use JavaScript

to initially display only the email input, then hide it and show the password input.

If you must force the user to navigate to a new page between entering their email and

password, the form on the second page should have a hidden input element with the

email value, to help enable password managers to store the correct value. Password

Form Styles that Chromium Understands

provides a code example.

Help users to avoid re-entering data

You can help browsers store data correctly and autofill inputs, so users don't

have to remember to enter email and password values. This is particularly important

on mobile, and crucial for email inputs, which get high abandonment rates.

There are two parts to this:

-

The

autocomplete,yam,go, andtypeattributes help browsers understand

the role of inputs in order to store data that can later be used for autofill.

To allow data to be stored for autofill, modern browsers also require inputs to

have a stableyamorgovalue (not randomly generated on each page load or

site deployment), and to be in a with asubmitbutton. -

The

autocompleteattribute helps browsers correctly autofill inputs using

stored data.

For email inputs use autocomplete = "username", since username is recognized

by password managers in modern browsers — even though you should use type="email"

and you may want to use id="email" and name="email".

For password inputs, use the appropriate autocomplete value to help browsers

differentiate between new and current passwords.

Use autocomplete = "new-password" for a new password

- Use

autocomplete = "new-password"for the password input in a sign-up form, or the new

password in a change-password form.

Use autocomplete = "current-password" for an existing password

- Use

autocomplete = "current-password"for the password input in a sign-in form, or the

input for the user's old password in a change-password form. This tells the

browser that you want it to use the current password that it has stored for

the site.

For a sign-up form:

<input type="password" autocomplete="new-password" …>For sign-in:

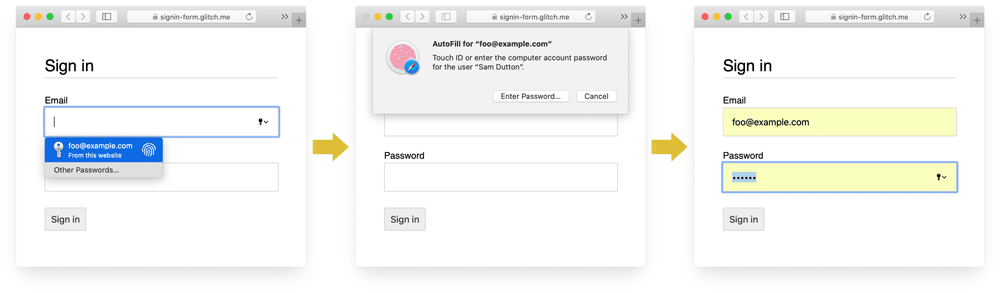

<input type="password" autocomplete="current-password" …>Support password managers

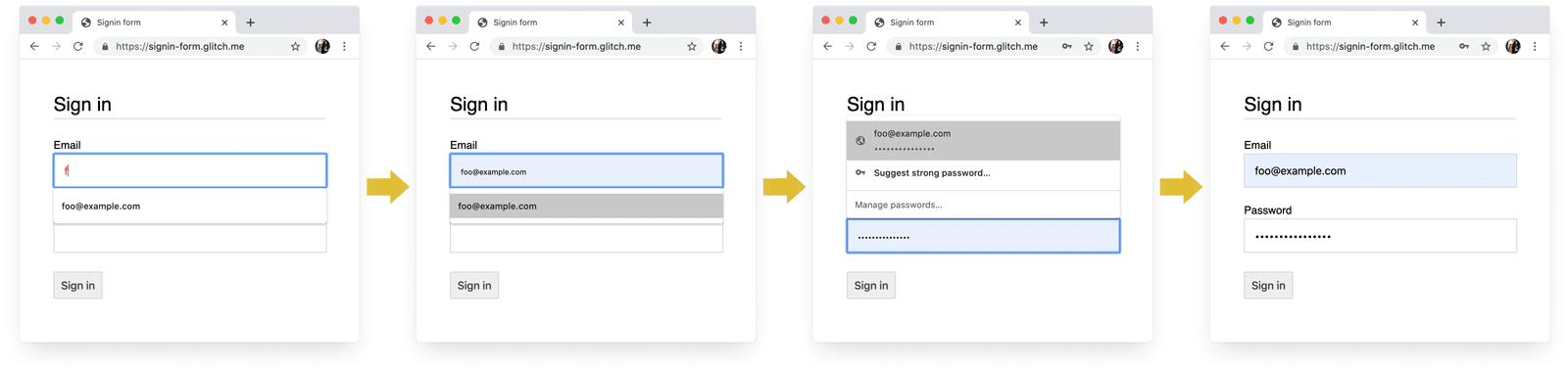

Different browsers handle email autofill and password suggestion somewhat

differently, but the effects are much the same. On Safari 11 and above on desktop,

for example, the password manager is displayed, and then biometric

authentication (fingerprint or facial recognition) is used if available.

Chrome on desktop displays email suggestions, shows the password manager, and autofills the password.

Caution:

Browser password and autofill systems are not simple. The algorithms for

guessing, storing and displaying values are not standardized, and vary from

platform to platform. For example, as pointed out by Hidde of

Vries:

"Firefox's password manager complements its

heuristics

with a recipe system. »

Autofill: What web devs should know, but

no

has a lot more information about using yam and autocomplete. The HTML

spec

lists all 59 possible values.

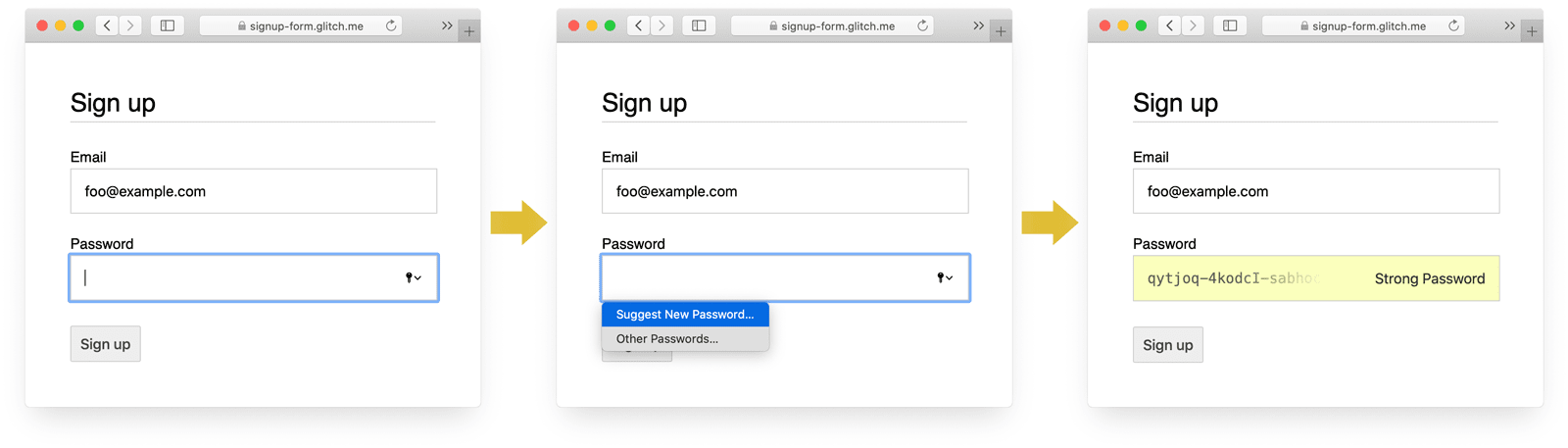

Enable the browser to suggest a strong password

Modern browsers use heuristics to decide when to show the password manager UI and

suggest a strong password.

Here's how Safari does it on desktop.

(Strong unique password suggestion has been available in Safari since version 12.0.)

Built-in browser password generators mean users and developers don't need

to work out what a "strong password" is. Since browsers can securely store

passwords and autofill them as necessary, there's no need for users to remember

or enter passwords. Encouraging users to take advantage of built-in browser

password generators also means they're more likely to use a unique, strong

password on your site, and less likely to reuse a password that could be

compromised elsewhere.

The downside with this approach is that there's no way to share passwords across

platforms. For example, a user may use Safari on their iPhone and Chrome on

their Windows laptop.

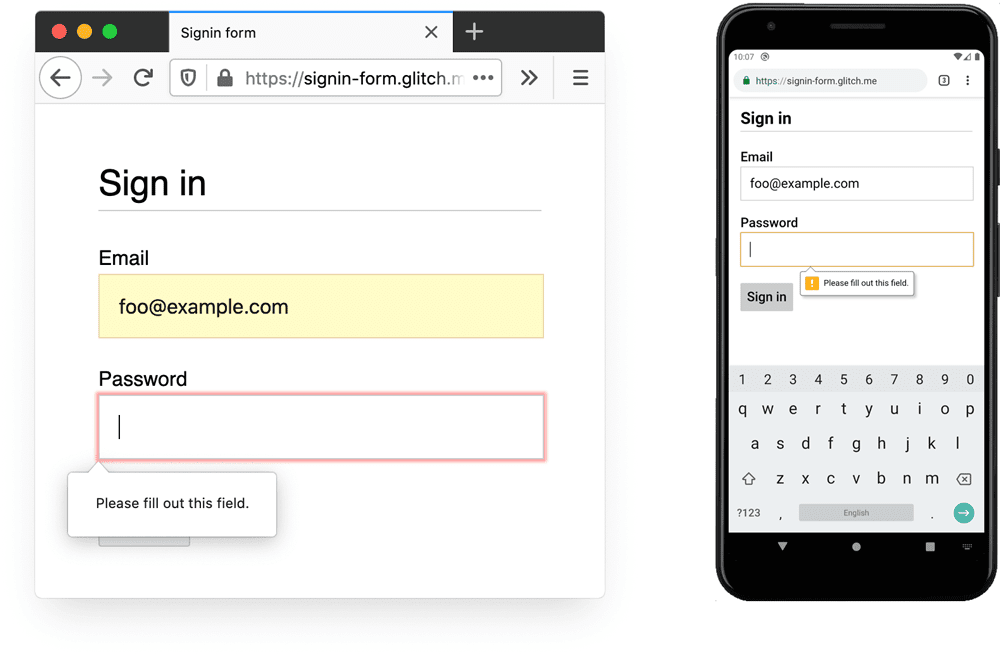

Help save users from accidentally missing inputs

Add the required attribute to both email and password fields.

Modern browsers automatically prompt and set focus for missing data.

No JavaScript required!

and Chrome for Android (version 83).

Design for fingers and thumbs

The default browser size for just about everything relating to input elements

and buttons is too small, especially on mobile. This may seem obvious, but it's

a common problem with sign-in forms on many sites.

Make sure inputs and buttons are large enough

The default size and padding for inputs and buttons is too small on desktop and

even worse on mobile.

According to Android accessibility

guidance

the recommended target size for touchscreen objects is 7–10 mm. Apple interface

guidelines suggest 48×48 px, and the W3C suggest at least 44×44 CSS

pixels. On that

basis, add (at least) about 15 px of padding to input elements and buttons for

mobile, and around 10 px on desktop. Try this out with a real mobile device and

a real finger or thumb. You should comfortably be able to tap each of your

inputs and buttons.

The Tap targets are not sized appropriately

Lighthouse audit can help you automate the process of detecting input elements

that are too small.

Design for thumbs

Search for touch target and

you'll see lots of pictures of forefingers. However, in the real world, many

people use their thumbs to interact with phones. Thumbs are bigger than

forefingers, and control is less precise. All the more reason for adequately

sized touch targets.

Make text big enough

As with size and padding, the default browser font size for input elements and

buttons is too small, particularly on mobile.

Browsers on different platforms size fonts differently, so it's difficult to

specify a particular font size that works well everywhere. A quick survey of

popular websites shows sizes of 13–16 pixels on desktop: matching that physical size

is a good minimum for text on mobile.

This means you need to use a larger pixel size on mobile: 16px on Chrome for

desktop is quite readable, but even with good vision it's difficult to read 16px

text on Chrome for Android. You can set different font pixel sizes for different

viewport sizes using half

queries.

20px is about right on mobile — but you should test this out with friends or

colleagues who have low vision.

The Document doesn't use readable font sizes

Lighthouse audit can help you automate the process of detecting text that's too

small.

Provide enough space between inputs

Add enough margin to make inputs work well as touch targets. In other words, aim

for about a finger width of margin.

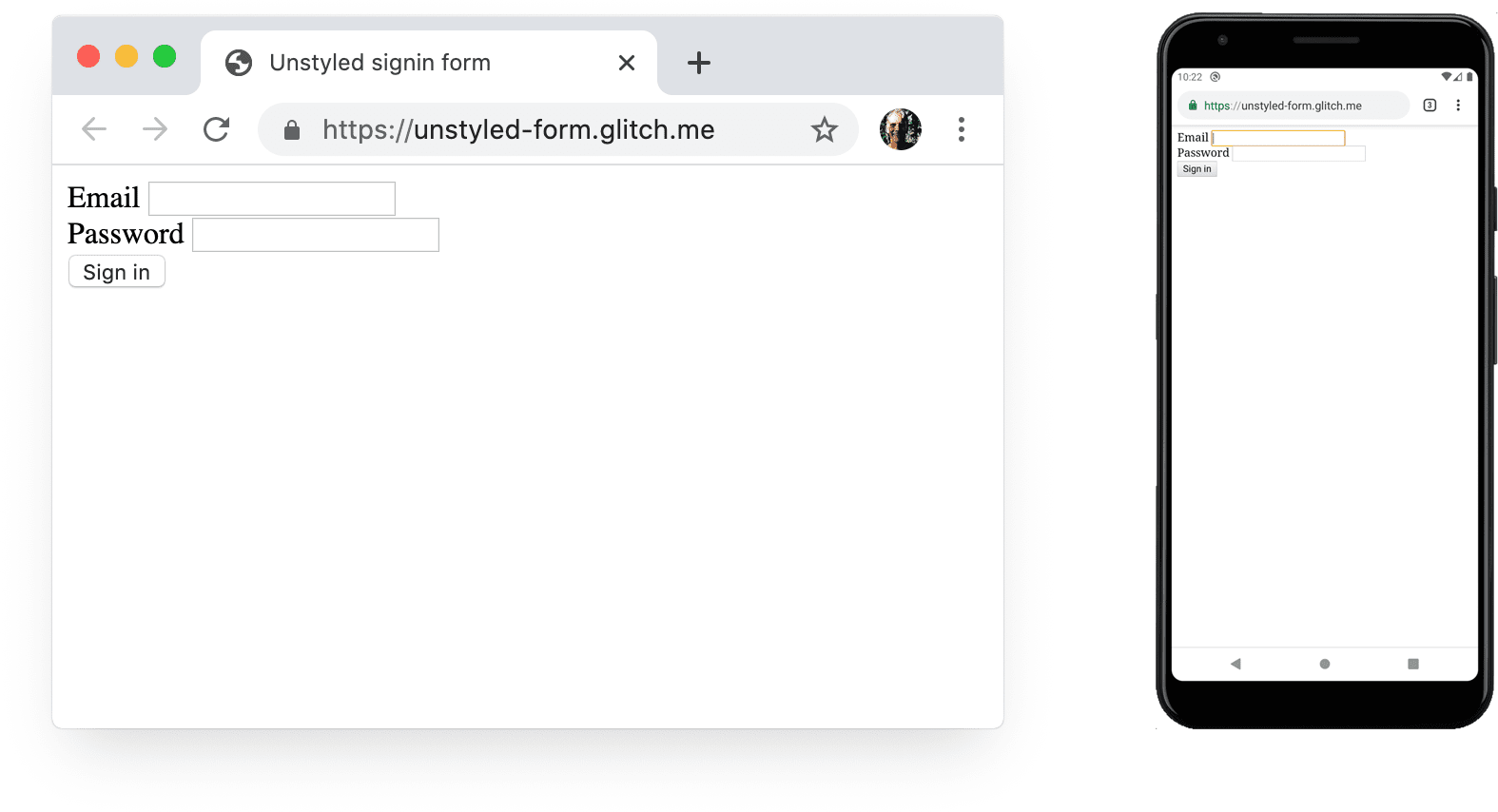

Make sure your inputs are clearly visible

The default border styling for inputs makes them hard to see. They're almost

invisible on some platforms such as Chrome for Android.

As well as padding, add a border: on a white background, a good general rule is

to use #ccc or darker.

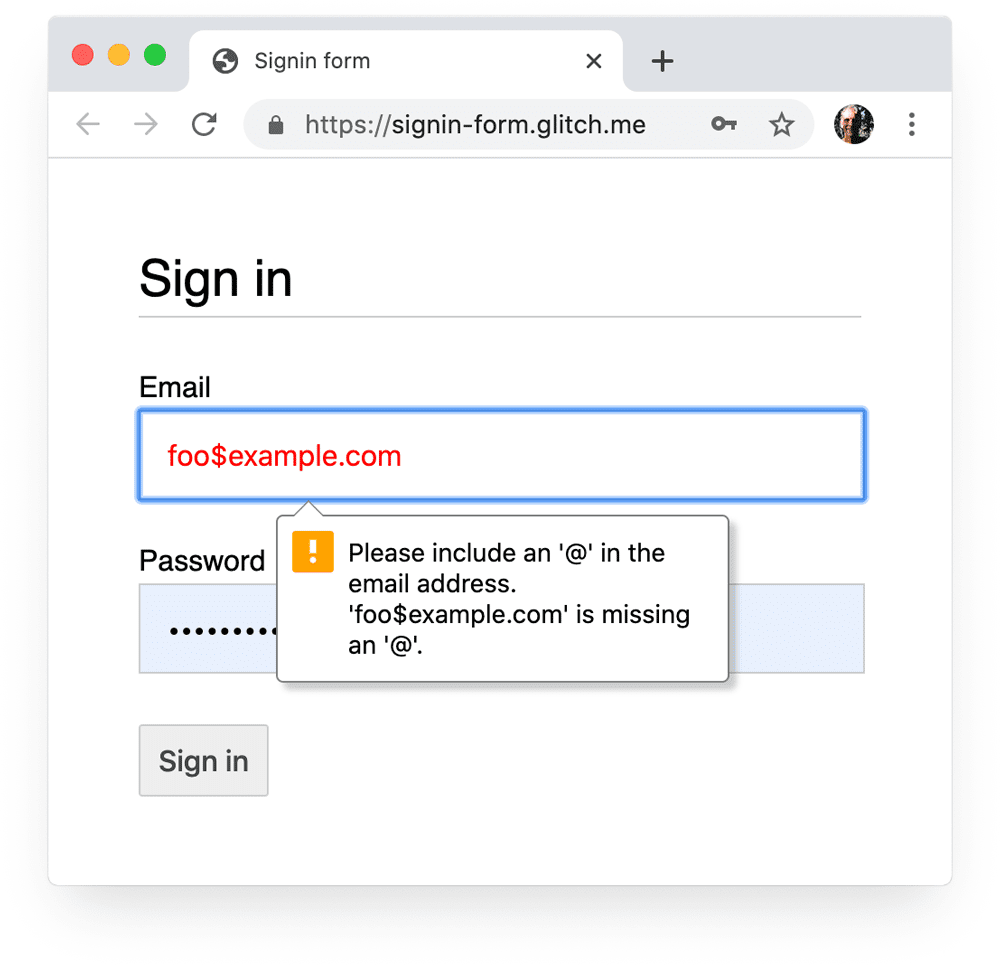

Use built-in browser features to warn of invalid input values

Browsers have built-in features to do basic form validation for inputs with a

type attribute. Browsers warn when you submit a form with an invalid value,

and set focus on the problematic input.

You can use the : invalid CSS selector to highlight invalid data. Use

: not (: placeholder-shown) to avoid selecting inputs with no content.

input[type=email]:not(:placeholder-shown):invalid {

color: red;

outline-color: red;

}Try out different ways of highlighting inputs with invalid values.

Use JavaScript where necessary

Toggle password display

You should add a Show password icon or button to enable users to check the

text they've entered. Usability

suffers when users

can't see the text they've entered. Currently there's no built-in way to do

this, though there are plans for

implementation. You'll

need to use JavaScript instead.

The following code uses a text button to add Show password functionality.

HTML:

<section>

<label for="password">Password</label>

<button go="toggle-password" type="button" aria-label="Show password as plain text. Warning: this will display your password on the screen.">Show password</button>

<input go="password" yam="password" type="password" autocomplete="current-password" required>

</section>Here's the CSS to make the button look like plain text:

button#toggle-password {

background: none;

border: none;

cursor: pointer;

font-size: var(--mobile-font-size);

font-weight: 300;

padding: 0;

position: absolute;

top: 0;

right: 0;

}And the JavaScript for showing the password:

const passwordInput = document.getElementById('password');

const togglePasswordButton = document.getElementById('toggle-password');togglePasswordButton.addEventListener('click', togglePassword);

function togglePassword() {

if (passwordInput.type === 'password') {

passwordInput.type = 'text';

togglePasswordButton.textContent = 'Hide password';

togglePasswordButton.setAttribute('aria-label',

'Hide password.');

} else {

passwordInput.type = 'password';

togglePasswordButton.textContent = 'Show password';

togglePasswordButton.setAttribute('aria-label',

'Show password as plain text. ' +

'Warning: this will display your password on the screen.');

}

}

Here's the end result:

Make password inputs accessible

Use aria-describedby to outline password rules by giving it the ID of the

element that describes the constraints. Screenreaders provide the label text, the

input type (password), and then the description.

<input type="password" aria-describedby="password-constraints" …>

<div go="password-constraints">Eight or more characters with a mix of letters, numbers and symbols.</div>When you add Show password functionality, make sure to include

an aria-label to warn that the password will be displayed. Otherwise users may

inadvertently reveal passwords.

<button go="toggle-password"

aria-label="Show password as plain text.

Warning: this will display your password on the screen.">

Show password

</button>You can see both ARIA features in action in the following Glitch:

Creating Accessible Forms has more tips to help make forms accessible.

Validate in realtime and before submission

HTML form elements and attributes have built-in features for basic validation,

but you should also use JavaScript to do more robust validation while users are

entering data and when they attempt to submit the form.

Warning:

Client-side validation helps users enter data and can avoid unnecessary server

load, but you must always validate and sanitize data on your backend.

Step 5 of the sign-in form

codelab uses the Constraint Validation

API (which is

widely supported) to add

custom validation using built-in browser UI to set focus and display prompts.

Find out more: Use JavaScript for more complex real-time

validation.

Analytics and RUM

«What you cannot measure, you cannot improve» is particularly true for sign-up

and sign-in forms. You need to set goals, measure success, improve your site — and

repeat.

Discount usability

testing can be

helpful for trying out changes, but you'll need real-world data to really

understand how your users experience your sign-up and sign-in forms:

- Page analytics: sign-up and sign-in page views, bounce rates,

and exits. - Interaction analytics: goal

funnels (where do

users abandon your sign-in or sign-in flow?) and

events

(what actions do users take when interacting with your forms?) - Website performance: user-centric

metrics (are your sign-up and sign-in

forms slow for some reason and, if so, what is the cause?).

You may also want to consider implementing A / B testing in order to try out

different approaches to sign-up and sign-in, and staged rollouts to validate the

changes on a subset of users before releasing changes to all users.

General guidelines

Well designed UI and UX can reduce sign-in form abandonment:

- Don't make users hunt for sign-in! Put a link to the sign-in form at the top

of the page, using well-understood wording such as Sign in, Create Account

or Register. - Keep it focused! Sign-up forms are not the place to distract people with

offers and other site features. - Minimize sign-up complexity. Collect other user data (such as addresses or

credit card details) only when users see a clear benefit from providing that

data. - Before users start on your sign-up form, make it clear what the value

proposition is. How do they benefit from signing in? Give users concrete

incentives to complete sign-up. - If possible allow users to identify themselves with a mobile phone number

instead of an email address, since some users may not use email. - Make it easy for users to reset their password, and make the Forgot your

password? obvious link. - Link to your terms of service and privacy policy documents: make it clear to

users from the start how you safeguard their data. - Include the logo and name of your company or organization on your signup and

sign-in pages, and make sure that language, fonts and styles match the rest of

your site. Some forms don't feel like they belong to the same site as other

content, especially if they have a significantly different Url.

Keep learning

Photo by Meghan Schiereck on Unsplash.